Content warning: I make a lot of wrong assumptions about the identity of the mushroom in this blog, before I eventually come to a conclusion I have a reasonable amount of confidence in.

The main reason we were on the Isle of Iona (see previous post about its waxcaps) was to take a trip to Staffa.

|

View of Staffa as the boat approaches from Iona.

|

The boat trip from Iona gives you one hour to explore the island which rises out of the North Atlantic Ocean like a giant basalt cathedral. One hour.

While our shipmates formed an orderly queue to see Fingal's Cave, we raced up the steps to explore the island. Surrounded by a dramatic, rocky coastline, Staffa has a grassy, heathy cap which I figured MUST have some mushrooms on it.

At the side of an inauspicous-looking path, I spotted one small patch of waxcaps...

... hiding in the long grass.

Bright sunshine illuminated the scales on the cap of this little red mushroom.

Underneath, pale yellow (adnate / adnexed?) gills, which looked almost white in the sunshine, contrasted with the red cap and smooth stipe.

There was no time for closer observation in the field. We had to leg it back down to sea level or we'd miss our chance to see Fingal's Cave and the boat back to Iona.

Fingal's Cave was amazing and impossible to photograph in five minutes with a phone, and the light outside blazing...

Returning to the boat we noticed the reddish-brown jellyfish hanging in the water, close to where it laps against these basalt columns. But there was no time to stand and stare, or get a better snap.

Back on the boat, I remembered the mushrooms I'd hurriedly thrust into my pocket earlier on.

One specimen looked to have dark grey scales at the centre of the cap.

Being in my pocket hadn't done them any good, but I could still make out this specimen has adnate gills.

Hoping no one was watching, I gave them a good sniff. Nothing.

I thought they were probably Hygrocybe miniata and, reading back through the descriptions in Boertmann's book (The Genus Hygrocybe, 2nd Edition), they are described as having "squamules concolorous and becoming yellow after slight drying, very rarely dark greyish in the centre" - which sounded about right. That species has distinctively pear-shaped ('mitriform') spores so I thought I'd take a look to confirm.

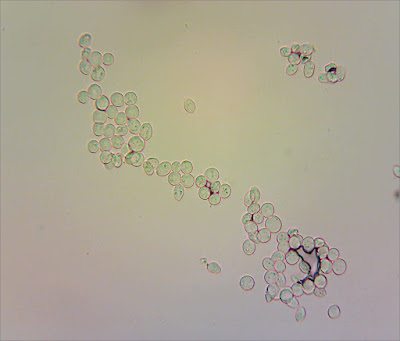

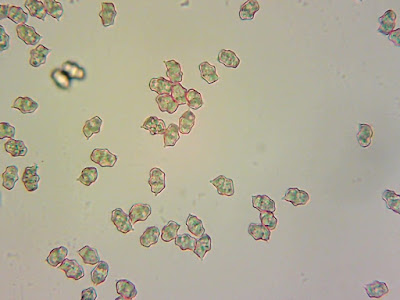

I'm still struggling with preparing microscope slides with dried material - and these were particularly squashed and broken by the time I got them home - so I tried a new approach: putting a drop of ammonia on a slide and just washing a couple of gills in it, to see if some spores would float off. It worked!

The following images are all captured at 400x magnification.

I found plenty of spores floating around. But none of them look mitriform to me. So I think that rules out

H. miniata.Hmm.

I started again from the beginning with Boertmann's key, and found myself getting into some seriously tricky territory - these little red waxcaps can be rather cryptic.

Could I have found Hygrocybe calciphila? Spore shape appears to be a better match. Boertmann says it's "generally rare, but may be overlooked" and describes it as known to occur on "basic (basalt or gypsum) soils"; I think it's probably a safe bet that the soil on Staffa is basalt-y!

Hygrocybe calciphila seems like the best fit with everything I've observed. But given it's so rarely recorded (and a new species to me) it would be good to get it confirmed by someone who knows what they're doing. Or perhaps an ITS barcode...

Update 24/09/2022

I got an email from Andy McLay, Natural England's waxcap expert, advising me to compare my collection with Garlic Waxcap Hygrocybe helobia. I think I ruled this out because I didn't get the faint smell of garlic ... but that was really an oversight on my part.

Hygrocybe helobia is fairly distinct in its microscopic characteristics, having a regular gill trama with long, slender elements.

I should get in the habit of checking gill trama characteristics - looking at a cross-section of the gills in thin-section - but the truth is I'm not very good at preparing the thin-sections so I avoid doing it.

I am reasonably confident, having spent quite-a-long-time looking at some squashes from my collection under the microscope, it has a regular gill trama.

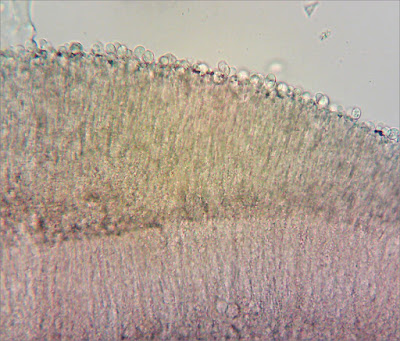

|

Gill trama, from dried material. 400x magnification mounted in ammonia and stained with Congo Red.

|

So I think there is good evidence here for going with Andy McLay's suggestion that what I've got here is Hygrocybe helobia. That would fit with the spore shape being rather variable. Another feature of H. helobia that Boertmann mentions in his description is that the flesh is very fragile - that's something I observed as my collection broke into pieces almost as soon as I touched it.Thanks Andy!

***

Couldn't resist one more try at getting a decent gill trama squash. I think this one's better:

|

100x magnification. Gill cross-section mounted in water and stained (carefully!) with Congo Red.

|

|

Same as above, at 400x magnification. I am confident I can see long slender elements here, with tapering ends.

|

For the record

Date: 5 September 2022

Location: Staffa

Record will be entered into iRecord in due course, if I get a decent fix on what species it is!